A Fox news broadcast about the state of our highways and why high speed rail might be a good thing.

https://www.infrastructurist.com/2010/12/06/is-us-infrastructure-falling-dangerously-behind-the-pundits-discuss/

Gotham Cycle Chic, Circa 1896

from How We Drive, the Blog of Tom Vanderbilt’s Traffic by Tom Vanderbilt

Continue reading “Gotham Cycle Chic, Circa 1896”

Build more highways, get more traffic

By Randy Salzman

Although a Daily Progress editorial thinks otherwise, data from around the country is clear: When you build additional highways, you quickly create more traffic congestion.

Every highway project has different effects, but overall the data illustrates that more lanes of highway induce more people to drive more times and more places, until not only is any new roadway oversubscribed but the roadways it was intended to relieve are again backed up. A 1998 Surface Transportation Policy Project titled “If you Built it, They Will Come: Why We Can’t Build Ourselves Out of Congestion” found that 90 percent of new urban roadways in America are overwhelmed within five years.

A different analysis of 70 urban areas across 15 years concluded:

“Metro areas that invested heavily in road capacity expansion fared no better in easing congestion than metro areas that did not. Trends in congestion show that areas that exhibited greater growth in lane capacity spent roughly $22 billion more on road construction than those that didn’t, yet ended up with slightly higher congestion costs per person, wasted fuel, and travel delay… . On average the cost to relieve the congestion reported by TTI [Texas Transportation Institute] just by building roads could be thousands of dollars per family per year.

…

Unfortunately for those of us who want our tax dollars spent wisely, as both a nation and a community we’re invested in out-dated, short-term thinking. Media rarely understand or report the whole story of the American “love affair with the automobile.”

But even without the full story, all of us need to understand this: It is not population growth that creates congestion, it is new driving — which grows at an annual rate at least twice population, regardless of where the rate is measured. Since 1970, U.S. vehicle miles traveled have increased 121 percent — four times population growth.

If you think this is a chicken-and-egg problem, consider: “A 2000 study of 26 years of transportation data determined that one-third of all new road capacity in the Baltimore/Washington area has been used up by new travel that wouldn’t have occurred without highway expansion,” a 2002 report noted. “Between 64 percent and 94 percent of properties in nine Maryland highway corridors were developed after the completion of the highway — a clear demonstration of how highway construction can alter land-use patterns.”

In 2004, a study of the entire Mid-Atlantic region found “changes in lane-miles precede changes in travel” and a meta-analysis of dozens of studies found that, on average, a 10 percent increase in lane miles induces an immediate 4 percent increase in vehicle miles traveled, which climbs to 10 percent — the entire new capacity — in a few years.

Please note that these studies are all past tense. In future tense, construction advocates apply today’s driving rates to a simplistic formula and claim that “X minutes of savings per driver” will accrue due to the new highway. Although politicians and transportation boards rarely compare figures after expensive construction projects are complete, those projected time savings never exist in any post-construction analysis.

…

Continue reading “Build more highways, get more traffic”

CWL 2010 #4 Pricing Driving

from TheWashCycle by washcycle

I’ve been dreading writing this one because I fear it will be viewed as some sort of “War on Drivers” kind of thing. I’m frequently a driver these days, so I certainly don’t want to declare war on myself. But, to be frank, if we’re going to get more cyclists we’re going to have to have fewer of something else (or more total trips – it is true that bike sharing systems create trips where people would have just stayed at home, but that is really a niche). The best place, from a social cost standpoint to get cyclists from is the current pool of drivers. One way to do that, without it being some sort of “war on drivers,” is to properly price the cost of driving, which would encourage some fence sitters to save money by biking, walking, taking metro, etc…There are several ways we subsidize driving that could be addressed.

The gas tax: The federal gas tax has been stuck at 18.4 cents per gallon since 1993. With inflation that means we’ve been cutting the tax every year. The Federal Highway Trust Fund, which gets ~2/3rds of its revenue from the gas tax, has recently been running at a deficit, and our roads have billions of dollars of deferred maintenance. Just indexing the current tax to inflation would go a long way toward solving the problem, but if we want the gas tax to continue to fill the gap in the FHTF, it will probably need to be increased. On the one hand, 81% of people say they’d pay more taxes to repair and upgrade our infrastructure, but almost the same percentage said they’d oppose an increase to the gas tax. So that’s a mixed message.

Furthermore, you could make a case that the tax should be increased to cover the environmental costs of mining, shipping, refining and burning gasoline. Some have even argued that the gas tax is a fair way to pay for the Iraq war. An analysis done in 1998 showed that to capture the full cost of gasoline, the tax would need to be raised by several dollars per gallon. That is probably too extreme for most people.

Personally I’d like to see us move to a Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) tax to cover the costs of roads and infrastructure, with a multiplier for car weight; and a gas tax to cover some clean air, clean water and alternative fuel initiatives. But that is probably not going to happen.

…

The Motorist’s Identity Crisis

Author: Brian Ladd

Bicyclists and transit riders are losers – right? Or are they elitist, sneering yuppies? Brian Ladd says that people’s attitudes and transportation choices are shaped by deep-seated feelings about respectability, and it planners should pay attention.

Non-motorists often wonder why drivers seem so oblivious to their needs and even their safety. Todd Litman’s recent Planetizen post on “The Selfish Automobile” argues persuasively that motorists’ sense of entitlement has grown out of plans and hidden subsidies that stack the deck in their favor, while appearing to do the opposite. Automobile dependence, as he describes it, has structural causes and psychological effects. Attitudes, though, can carry their own power. Auto-centered planning and auto-centered lives have made it hard for American motorists even to imagine alternative transportation. The idea of getting around without a car has been just too frighteningly gauche to contemplate. But that may be changing.

Most Americans know one thing about the bicyclists they see on the roads: they are losers, and you thank God you’re not one of them. Who, after all, rides bikes (at least for transportation, not recreation) in the United States? Mostly kids who aren’t old enough to drive—and not even so many of them anymore. Adult cyclists are seen as people too poor to own a car, or too dysfunctional to have a license: grizzled misfits and dark-skinned immigrants you see wobbling along the side of your suburban highway as you zoom past their elbows. Hollywood, as Tom Vanderbilt has shown in a recent Slate article, powerfully reinforces this contempt for the carless.

Most Americans know one thing about the bicyclists they see on the roads: they are losers, and you thank God you’re not one of them. Who, after all, rides bikes (at least for transportation, not recreation) in the United States? Mostly kids who aren’t old enough to drive—and not even so many of them anymore. Adult cyclists are seen as people too poor to own a car, or too dysfunctional to have a license: grizzled misfits and dark-skinned immigrants you see wobbling along the side of your suburban highway as you zoom past their elbows. Hollywood, as Tom Vanderbilt has shown in a recent Slate article, powerfully reinforces this contempt for the carless.

The reality of biking and bikers is, of course, more complicated. But even the fantasy is more complicated. In American cities with newly thriving bike cultures, cyclists have acquired an entirely different image: as arrogant yuppies. Just look at the letters column or the comments thread any time a daily newspaper publishes a story about bike lanes or shared streets. One motorist after another rages against the privileged spandex crowd that interferes with ordinary working stiffs trying to drive to work: They should be banned from the roads! The police need to crack down on them! Why do we have to get licenses and pay taxes, while they don’t? Life is so unfair for us motorists! The venom is often shocking, but the sentiments are heartfelt–even if a cyclist, just home from her daily brush with death, can only shake her head in disbelief.

But wait: weren’t motorists the superior ones? Who’s sneering at whom here? Could it be that motorists are sitting a little uneasily in their driver’s seats? It’s harder to dismiss cyclists as beneath contempt when you suspect that they might just be contemptuous of you. What’s a poor motorist to think? They’ve always known that bicyclists are scum, but now they aren’t quite sure why.

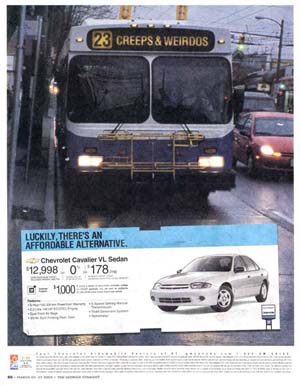

The same confusion applies to transit users. Here the dichotomy is older and clearer: buses versus trains. On the one hand, you have the image of the typical bus rider (outside of Manhattan and perhaps a few other exclusive locales): the definitive loser. According to a saying that circulates in England, and is often falsely attributed to Margaret Thatcher, a man who has reached the age of thirty and still rides the bus can count himself a failure in life. American bus riders, probably even more than their British counterparts, are painfully aware of what passing motorists think of them. After all, they learned it in high school, where the world divides between kids with cars and those condemned to ride to school in the yellow “loser cruiser.”

When a Los Angeles bus rider asked presidential candidate George W. Bush about transit improvements in 2000, Bush responded, “My hope is that you will be able to find good enough work so you’ll be able to afford a car.” Bush was undoubtedly sincere. Like many Americans—probably most—he saw a bus (like a bicycle) as a nothing more than a pathetic substitute for a car.

On the other hand, the commuter train has survived the entire auto age in several of our older cities, and its clientele has held onto its moderately exclusive image. In the long-vanished age of the “family car”—that is, when there was only one per family—the suburban housewife dropped off her suit-clad husband at the rail station, so she could have the station wagon (that’s where the name comes from) for the day. Most suburban commuter lines still do, in fact, serve a fairly upscale clientele: just look at the parking lots. Meanwhile, many U.S. cities without these legacy systems are building new light-rail lines, which are clearly angling for prosperous riders who either own cars or could afford them. Even where these lines are not claiming street space from cars, they are competing for scarce transportation dollars that could be used to build roads. Understandably, some motorists are suspicious of—or simply bewildered by–what appear to be efforts to make mass transit fashionable.

It is easy for number-crunching economists and planners to ignore the power of fashion, but we do so at our peril. People’s attitudes and transportation choices are shaped by deep-seated feelings about respectability. This is not to suggest that the practical advantages of cars (whether dependent on subsidies or not) don’t matter. They have made it easy for American motorists to avoid contemplating their transportation choices. If at all possible, you drive. Anything else seems inconvenient, uncomfortable–and certainly embarrassing. So the average driver, like the apocryphal Margaret Thatcher and the real George W. Bush, finds bicyclists and bus riders either pitiful or incomprehensible–and politicians cannot resist demonizing bike-friendly policies.

But if cyclists and transit users no longer seem to envy motorists, then motorists might be facing a crisis of confidence. In the short run, their insecurity may harden attitudes, as anxious drivers cling to their steering wheels and rage against the trendsetters. But change may be coming. If teenagers’ desire to drive continues to weaken, if Hollywood begins to give bikes and buses a trendy aura, we will know that the tides of fashion are changing. If cars cease to be the essential token of respectability—if you can be cool without one—then the automakers may be in deeper trouble than they think.

For a long time to come, cars will remain the most practical choice for many people. But motorists’ anger and defensiveness may itself be evidence of a cultural revolution in the making.

Brian Ladd is an urban historian and author of the book Autophobia: Love and Hate in the Automotive Age.

A conversation with a traffic engineer [video]

found via Greater Greater Washington

[B’ Spokes: Like GGW I too had conversations like this. It’s rather scary to realize when a traffic engineer wants to “improve safety” they mean first induce faster driving then make it safer for the speeding motorists and less safe for everyone else.]

House Passes Extension of Transportation Reauthorization

…

An extension of current programs and funding levels is a far cry from my preferred approach to addressing the nation’s growing surface transportation challenges. Meeting the overall needs of the system and developing a 21st Century surface transportation network worthy of being passed on to future generations can only be accomplished through the passage of a robust and transformational long-term surface transportation authorization act.

However, extending these programs through the end of the fiscal year will provide States, localities, and public transit agencies with the degree of certainty necessary to move forward with their capital programs while Congress continues to work toward passage of a long-term surface transportation authorization bill.

…

Continue reading “House Passes Extension of Transportation Reauthorization”

Why Doesn’t Someone Tell You to Drive Less?

from Streetsblog All Posts by Angie Schmitt

When you become a new parent you are told many things. “By far the biggest killer of children is car crashes” isn’t one of them. In St. Louis you’re told there’s an outbreak of Whooping Cough. You’re told not to let too many people hold the baby given that it’s flu season. You’re told that purple feet are OK, but a purple face is not. You’re told to not tie blue balloons to your front porch handrail, lest you attract child abductors. Why doesn’t someone tell you to drive less with your child in the car?

We’re told about threats to our children from outside the home, but not about those we inflict ourselves. We’re not told to change much of anything other than to buy a certified car seat and read the instructions. It’s incredibly important that a proper child seat is used. An online search for child car seats returns millions of results, most with a variation of the following: “Using a child safety seat is the best protection you can give your child when traveling by car.” There are literally thousands and thousands of pages of advice on which car seat you should buy, diagrams of how to install the seat, how to determine at what height the shoulder straps should be set.

Continue reading “Why Doesn’t Someone Tell You to Drive Less?”

Why aren’t people screaming from the rooftops that this is dangerous?

…

Judy and Joe were on their way to one of his after school activities on the day of the crash. They were just a mile from their home when a young woman driving a Hummer and talking on her cell phone ran a red light and slammed into their vehicle.

Judy was fortunate to escape with only minor injuries. But Joe wasn’t as lucky. His side of the car took the brunt of the impact, and he died the next day at the hospital.

The loss stunned the Teater family–especially when they discovered that the driver who struck them was on the phone at the time of the crash.

"She passed six cars and a school bus that were stopped for the red light, and she did not see them," Judy said. "She was talking and looking straight ahead and didn’t see the cars passing in front of her."

…

Continue reading “Why aren’t people screaming from the rooftops that this is dangerous?”

Car commercials, anything but being stuck in traffic

Streets blog has a collection of car commercials and it really gets you to think, what are they trying to sell us? Random quotes from their article:

Combining wistful nostalgia for the country’s economic glories of the past and bright-eyed optimism for its eco-friendly techno-future, this Chevrolet ad reminds us that our past, present, and future all depend on a healthy US auto industry, even if the cost in dollars and lives seems high.

Lexus: “The Next Big Thing”

Billions of dollars of ads touting safety have helped convince Americans that the phrase “safe car” is no oxymoron, notwithstanding the roughly 380,000 crash deaths over the past decade. Here’s a Lexus ad that takes to a dizzying new level the myth that car technology will solve—any minute now—the problems that the car itself has created. Its suggestion that “a real driver in a real car reacting to a real situation without real consequences” is a real possibility fosters a false sense of safety among drivers that encourages dangerous risk-taking.

Dodge Charger: “Man’s Last Stand”

Chrysler stokes the gender wars with this ad suggesting that the American male may seem to have been tamed by the boss and neutered by the wife, but all that the rebel within needs to bust out is a $38K fully loaded Dodge Charger. The road is his last refuge, the one place where he can still be a manly man. He’ll “eat fruit” at home, but he won’t be a fruit in control of the kind of growling, ferocious muscle car that had its heyday back when men last really had it good.

Continue reading “Car commercials, anything but being stuck in traffic”