By Charles Marohn

…

In retrospect I understand that this was utter insanity. Wider, faster, treeless roads not only ruin our public places, they kill people. Taking highway standards and applying them to urban and suburban streets, and even county roads, costs us thousands of lives every year. There is no earthly reason why an engineer would ever design a fourteen foot lane for a city block, yet we do it continuously. Why?

The answer is utterly shameful: Because that is the standard.

In the engineering profession’s version of defensive medicine, we can’t recommend standards that are not in the manual. We can’t use logic to vary from a standard that gives us 60 mph design speeds on roads with intersections every 200 feet. We can’t question why two cars would need to travel at high speed in opposite directions on a city block, let alone why we would want them to. We can yield to public pressure and post a speed limit — itself a hazard — but we can’t recommend a road section that is not in the highway manual.

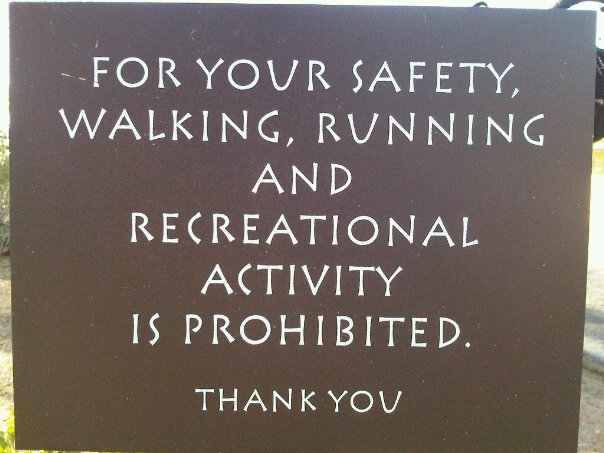

When the public and politicians tell engineers that their top priorities are safety and then cost, the engineer’s brain hears something completely different. The engineer hears, "Once you set a design speed and handle the projected volume of traffic, safety is the top priority. Do what it takes to make the road safe, but do it as cheaply as you can." This is why engineers return projects with asinine "safety" features, like pedestrian bridges and tunnels that nobody will ever use, and costs that are astronomical.

An engineer designing a street or road prioritizes the world in this way, no matter how they are instructed:

1. Traffic speed

2. Traffic volume

3. Safety

4. Cost

The rest of the world generally would prioritize things differently, as follows:

1. Safety

2. Cost

3. Traffic volume

4. Traffic speed

In other words, the engineer first assumes that all traffic must travel at speed. Given that speed, all roads and streets are then designed to handle a projected volume. Once those parameters are set, only then does an engineer look at mitigating for safety and, finally, how to reduce the overall cost (which at that point is nearly always ridiculously expensive).

In America, it is this thinking that has designed most of our built environment, and it is nonsensical. In many ways, it is professional malpractice. If we delivered what society asked us for, we would build our local roads and streets to be safe above all else. Only then would we consider what could be done, given our budget, to handle a higher volume of cars at greater speeds.

We go to enormous expense to save ourselves small increments of driving time. This would be delusional in and of itself if it were not also making our roads and streets much less safe. I’ll again reference a 2005 article from the APA Journal showing how narrower, slower streets dramatically reduce accidents, especially fatalities.

And it is that simple observation that all of those supposedly "ignorant" property owners were trying to explain to me, the engineer with all the standards, so many years ago. When you can’t let your kids play in the yard, let alone ride their bike to the store, because you know the street is dangerous, then the engineering profession is not providing society any real value. It’s time to stand up and demand a change.

It’s time we demand that engineers build us Strong Towns.

Continue reading “Confessions of a Recovering Engineer”

In the past there were claims that Secretary of Energy Steven Chu couldn’t commute by bike – as he used to in his previous job – because his security detail wouldn’t let him. That appears to not be true.